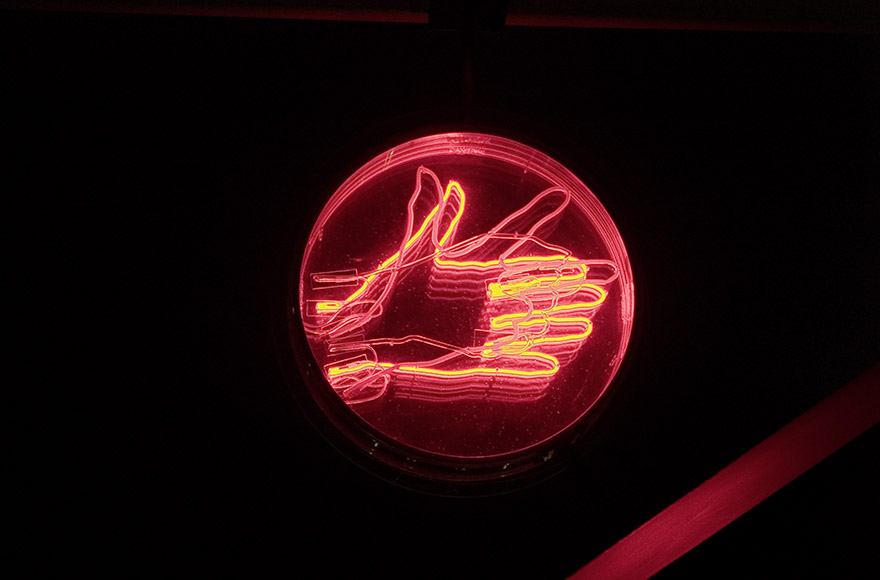

Randomized neonsigns marking the former frontier crossing point Oberbaumbridge Berlin. Realised in 1997. Commissioned by the Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment as a permanent marker on the Oberbaumbrücke, the former border crossing between East and West Berlin.

A neon game, powered by a random generator, marks the Oberbaumbrücke, the former border crossing between East and West Berlin. Two round light boxes made from acrylic, each with a diameter of 100 cm, are installed in the central spandrel of the elevated railway bridge above the river Spree. Inside each box are three curved neon tubes (yellow, red and blue) depicting the contours of hand movements. These are the gestures of the game “Rock paper scissors” to which the title refers: the red line forms an outstretched hand (paper), the yellow line shows splayed fingers (scissors) and the blue line forms the contours of a clenched fist (rock). Both fluorescent tube systems are switched on via photoelectric switches from dusk until 1 am. Powered by random generators, the hand movements change every six seconds. The objects are fairly nondescript and are supposed to be as commonplace as traffic signs. This is no sign visible from afar, but one that is integrated in the historic bridge as well as in the newly added centre piece. Rock beats scissors, scissors beats paper, paper beats rock— just like heads or tails, this game is played throughout the world in order to come to an agreement without having to argue about it. Owing to chance, one side is stronger or weaker than the other without generally being either. It is only the combination that causes one side to win or lose: rivalry, power games and trials of strength between two opponents are substantiated in an ironic way in Rock paper scissors. Two people stand opposite each other and try to come to a decision without argument or violence. By using this game of chance, the division of the city and the significance of the bridge as a border crossing between East and West Berlin from 1972 to 1989 are put in an artistic context. With reduced stylistic means, the work asks to what extent political decisions ultimately depend on chance, i.e. imply a moment of arbitrariness. Goldberg builds an imaginary bridge from past to present and raises politically explosive issues. Playfulness turns into ironic observations on the apparent inevitability of competition between political systems and its historical significance. It is a universally comprehensible installation.