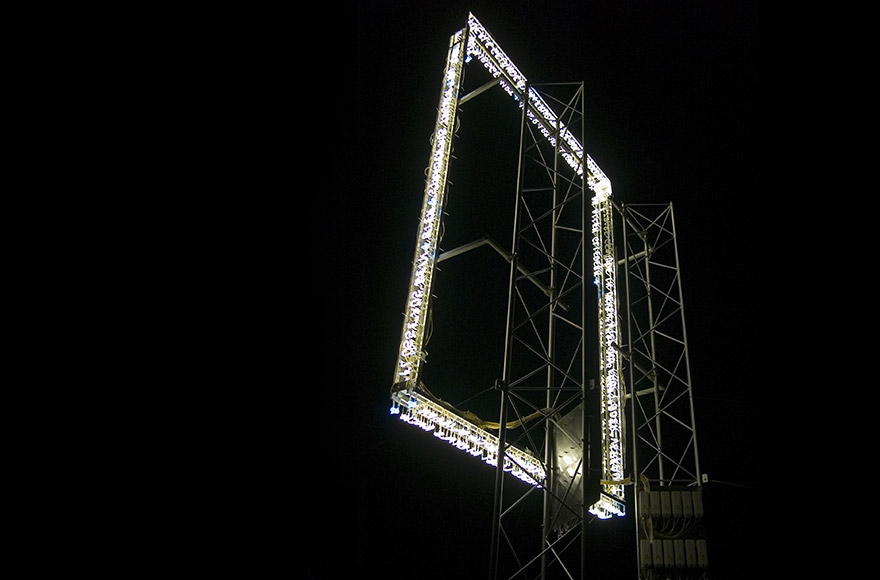

A steel profile frame with white and blue neon letters running around it and a round hole in the ground, realised as part of the Wiesbadener Kunstsommer “Wo bitte geht’s zum Öffentlichen?” (2006 Summer of Art, Wiesbaden, Germany “Show me the Way to the Public Sphere!”).

A steel profile frame measuring 450 x 350 x 20 cm, with white and blue neon letters running around it is mounted on two 11 m-high steel crossbeams. The construction is installed in front of a round hole in the ground (diameter: 10 m, depth 2 m, 45° gradient) covered in wildflowers and only accessible via a wooden ladder. The installation is located at the entrance to a large open area behind the main station in Wiesbaden, Germany. “Steel crossbeams, a metal frame, a partially overgrown hole in the ground. During the day Thorsten Goldberg’s work resembles an unfinished building site, a bad architectural investment on the noman’s-land behind the station which noone bothers to get rid of. At night, when functional, target-oriented life stops and the landscape of the euphemistically named “culture park” that is the transit area between the empty car park and the partying in the old abattoir surrenders as if half asleep to the darkness; only then does the message spelt out in white neon letters emerge like an apparition against the dark night sky.”*

The neon text which runs around the steel profile frame, which can only be seen from a contorted position, cites descriptions of the Land of Milk and Honey, for example from the 1491 „Sterfboeck” (Death Book): “RIVERS OF WINE + BEER + STREETS MADE FROM GINGER + NUTMEG + AND AN IDEAL LANDSCAPE + PRECIOUS BUILDING IN WHICH NO ONE BUYS OR SELLS + THERE ARE NO CRIPPLES OR BLIND PEOPLE, NO-ONE IS CROSS-EYED OR DUMB. NO-ONE SUFFERS FROM SCABIES OR HAS SPOTS, THERE ARE NO FREAKS + EVERYONE HAS A PERFECT BODY + AND THE VIGOUR OF MEN TO ENJOY THEIR WOMEN WILL NEVER FALTER +”.

The idea of the Land of Milk and Honey is based on legends describing a land where unfulfilled desires became real. As an ironic counterpart to the biblical paradise promising deliverance from all earthly matters, it entices us to fantasise about sensual and material things. Thorsten Goldberg’s neon sign promises just that: the establishment of the Land of Milk and Honey, a land of unlimited desires and uninhibited lust where children are born as adults and women remain forever virgins. This all too human dream with its visions of a fictitious land can be traced back to the Middle Ages. At the end of the 17th century, the imperial general Johann Andreas Schnebelin decribed the “Luilekkerland” as a land where one can find “all the vices of the waggish world, in particular kingdoms, estates and areas with many silly towns and cities (…) and many notions worth reading.”** Located next to some railway tracks in an area that has yet to undergo urban development, the construction promises a realm where all dreams come true, where gold can be found in the streets and penury is superseded by natural abundance. No-one needs to work, worry about how to pay the rent or suffer any other exertion. The status quo sustains itself, a sensual perpetuum mobile where idleness replaces progress and, in the last instance, animal instincts replace reflection. The construction of the object mimics a modern construction sign which announces a construction project at night in bright neon letters, visible from far away. The metal frame however, is empty. Where the construction sign should be, is nothing but the night sky. A window appears in the work rather than a projection screen, a window whose purpose is not the view but looking through itself. A wooden ladder leads down to the bottom of the strangely perfect hole densely covered in wild grasses. Down there in that almost romantically chaotic little meadow, as if cut out from a different place then transplanted here, the familiar surroundings disappear. The construction sign is a monument to longing which Kant defines as “an empty wish” (here the empty frame) and as “able to destroy the time between the desire and fulfilling that desire.”***

* Katharina Klara Jung, Milch + Honig +, in catalogue: Wo bitte geht’s zum Öffentlichen, Wiesbaden 2007.

** Cf. Johann Andreas Schnebelin’s late 17th century text: „Erklärung der Wunder=seltzamen Land = Charten Utopiae, so da ist/ das neu = entdeckte Schlaraffenland/ Worinnen All und jede Laster der schalckhafftigen Welt/ als besondere Königreiche/ Herrschaften und Gebiete/ mit vielen läppischen Städten/ Festungen/ Flecken und Dorffern/ Flüssen/ Bergen/ Seen/ Insuln/ Meer und Meer = Busen/ wie nicht weniger Dieser Nationen Sitten/ Regiment/ Gewerbe/ samt vielen leßwürdigen Einfällen aufs deutlichste beschrieben; Allen thörrechten Läster = Freunden zum Spott/ denen Tugend liebenden zur Warnung/ und denen melancholischen Gemüthern zu einer ehrlichen Ergetzung vorgestellet. Gedruckt zu Arbeitshausen/ in der Graffschafft Fleissig/ in diesem Jahr da Schlarraffenland entdecket ist”.

*** Immanuel Kant on anthropology and pedagogy: Schriften zur Anthropologie und Pädagogik, Leipzig 1839, p. 276.